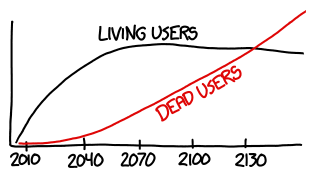

When, if ever, will Facebook contain more profiles of dead people than of living ones?

Emily Dunham

Either the 2060s or the 2130s.

There are not a lot of dead people on Facebook. The main reasons for this is that Facebook—and its users—are young. The average Facebook user has gotten older over the last few years, but the site is still used at a much higher rate by the young than by the old.[1]There are a zillion surveys confirming this, such as this one from eMarketer.

The Past:

Based on the site's growth rate, and the age breakdown of their users over time,[2]You can get user counts for each age group from Facebook's create-an-ad tool, although you may want to try to account for the fact that Facebook's age limits cause some people to lie about their ages. there are probably 10 to 20 million people who created Facebook profiles who have since died.

These people are, at the moment, spread out pretty evenly across the age spectrum. Young people have a much lower death rate than people in their sixties or seventies, but they make up a substantial share of the dead on Facebook simply because there have been so many of them using it.

The Future:

About 290,000 US Facebook users will die (or have died) in 2013. The worldwide total for 2013 is likely several million.[3]Note: In some of these projections, I used US age/usage data extrapolated to the Facebook userbase as a whole, because it's easier to find US census and actuarial numbers than to assemble the country-by-country for the whole Facebook-using world. The US isn't a perfect model of the world, but the basic dynamics—young people's Facebook adoption determines the site's success or failure while population growth continues for a while and then levels off—will probably hold approximately true. If we assume a rapid Facebook saturation in the developing world, which currently has a faster-growing and younger population, it shifts many of the landmarks by a handful of years, but doesn't change the overall picture as much as you might expect. In just seven years, this death rate will double, and in seven more years it will double again.

Even if Facebook closes registration tomorrow, the number of deaths per year will continue to grow for many decades, as the generation who was in college between 2000 and 2020 grows old.

The deciding factor in when the dead will outnumber the living is whether Facebook adds new living users—ideally, young ones—fast enough to outrun this tide of death for a while.

Facebook 2100:

This brings us to the question of Facebook's future.

We don't have enough experience with social networks to say with any kind of certainty how long Facebook will last. Most websites have flared up and then gradually declined in popularity, so it's reasonable to assume Facebook will follow that pattern.[4]I'm assuming, in these cases, that no data is ever deleted. So far, that's been a reasonable assumption; if you've made a Facebook profile, that data probably still exists, and most people who stop using a service don't bother to delete their profile. If that behavior changes, or if Facebook performs a mass purging of their archives, the balance could change rapidly and unpredictably.

In that scenario, where Facebook starts losing market share later this decade and never recovers, Facebook's crossover date—the date when the dead outnumber the living—will come sometime around 2065.

But maybe it won't. Maybe it will take on a role like the TCP protocol, where it becomes a piece of infrastructure on which other things are built, and has the inertia of consensus.

If Facebook is with us for generations, then the crossover date could be as late as the mid-2100s.

That seems unlikely. Nothing lasts forever, and rapid change has been the norm for anything built on computer technology. The ground is littered with the bones of websites and technologies that seemed like permanent institutions ten years ago.

It's possible the reality could be somewhere in between.[5]Of course, if there's a sudden rapid increase in the death rate of Facebook users—possibly one that includes humans in general—the crossover could happen tomorrow. We'll just have to wait and find out.

The fate of our accounts:

Facebook can afford to keep all our pages and data indefinitely. Living users will always generate more data than dead ones, and the accounts for active users are the ones that will need to be easily accessible. Even if accounts for dead (or inactive) people make up a majority of their users, it will probably never add up to a large part of their overall infrastructure budget.

More important will be our decisions. What do we want for those pages? Unless we demand that Facebook deletes them, they will presumably, by default, keep copies of everything forever. Even if they don't, other data-vacuuming organizations will.

Right now, next-of-kin can convert a dead person's Facebook profile into a memorial page. But there are a lot of questions surrounding passwords and access to private data that we haven't yet developed social norms for. Should accounts remain accessible? What should be made private? Should next-of-kin have the right to access email? Should memorial pages have comments? How do we handle trolling and vandalism? Should people be allowed to interact with dead user accounts? What lists of friends should they show up on?

These are issues that we're currently in the process of sorting out by trial and error. Death has always been a big, difficult, and emotionally charged subject, and every society finds different ways to handle it.

The basic pieces that make up a human life don't change. We've always eaten, learned, grown, fallen in love, fought, and died. In every place, culture, and technological landscape, we develop a different set of behaviors around these same activites.

Like every group that came before us, we're learning how to play those same games on our particular playing field. We're developing, through sometimes messy trial and error, a new set of social norms for dating, arguing, learning, and growing on the internet. Sooner or later, we'll figure out how to mourn.

Happy Halloween!